to whom do the dead belong

ode to a people

12” x 9” 2019

acrylic on chalkboard

“The avenging of a genocide should be manifested in the flourishing of a people.” -Meline Toumani, There Was & There Was Not

“Rememberance is a form of recognition and of honoring. Perhaps remembering the dead is the very opposite of gratuitous violence, a gratuitous retrieval of meaning from oblivion.” -Eva Hoffman, After Such Knowledge

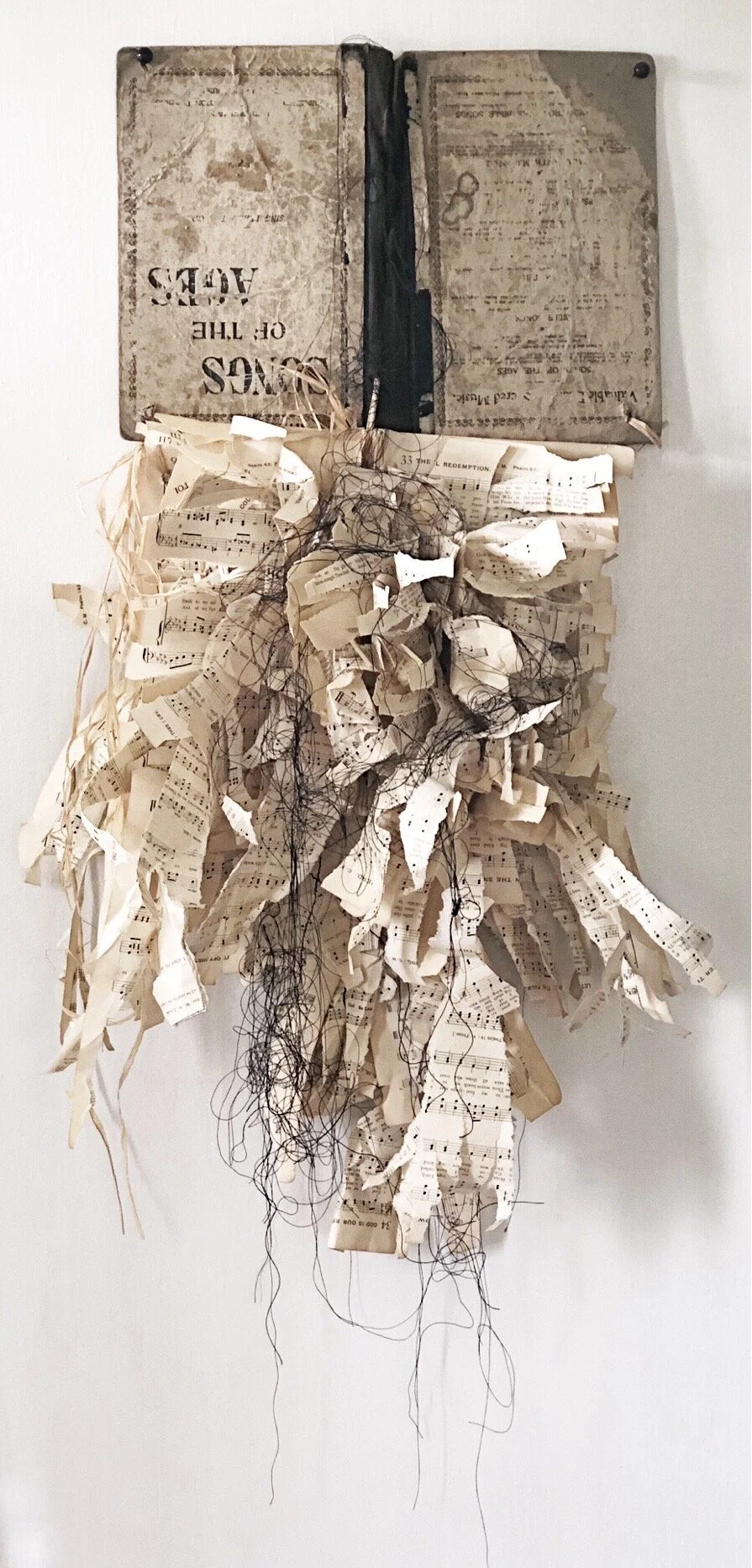

the return of the voice

26” x 10” 2019

hymnal & thread

[Genocide] is disbelieved because it does not enter and cannot be framed by any existent frame of reference, because our perception of reality is molded by frames of reference, what is outside them, however imminent and otherwise conspicuous, remains historically invisible, unreal and can only be encountered by a systematic disbelief. 108

preferring silence

29” x 10” 2020

hymnal, thread & acrylic on in wood frame

living through

29” x 10” 2020

acrylic & pen on canvas

to whom do the dead belong?

29” x 10” 2020

watercolor, acrylic, pastel, photo, thread & pen on canvas

“Issues of biography & history are neither simply represented or reflected but are reinscribed, translated, rethought & fundamentally worked over by the text.” -Shoshana Felman & Dori Laub

Because so much of my artistic practice deals with the intersection of image and text, I wanted to take the textual accounts of narrative and play with this idea visually. Much of the account is miraculous, but much of it is also completely horrifying. Certain lines are actually quite humorous: “He dislikes work -whenever he sees a flock of sheep he follows them for a little while.” Others are appalling and unimaginable: “I have not heard from any member of my family since 1919.” “We traveled through the deserts where you could see bleached bones of Armenians who were massacred in the great war.” “My brother and I are the only survivors of my entire family: our parents, 6 brothers and 3 sisters.”

I was haunted by another line from Feldman & Laub, that ‘the artist’s role is to demolish the deceptive image of history as abstraction.’ Reading through the entire account of my great grandfather’s escape to America and subsequent search for his family took away the abstraction, and I wanted to reinscribe the words of his search for his only surviving family member, his brother Krikor.

I am indebted to my cousin Aaron Telian for his compilation and organization of official government & immigration documents, personal letters, newspaper articles & photos in his senior project, The Krikor Story.

i was and i was not

8” x 7” 2020

hymnal, gesso, acrylic & colored pencil

The traditional first line of Armenian folk tales is: ‘There was and there was not.’ This opening is my heritage’s version of ‘once upon a time,’ and it speaks not only to the layers of complexity and the possibility of dualing narratives, but the complicitness of a narrator within the tale itself. Writer Meline Toumani says, “this [phrase] should not be taken to mean that all stories are equally true, but that all stories are imperfect.” Can an Armenian artist work with artistic objectivity? There is almost an inherent refusal of that notion; an irreconcilability between a burden of proof and the lack of genocide recognition. This project was an attempt to understand and to connect; to explore through my family history the idea of belonging to a community vs. attempting to individuate. Researching deep within the layers, sometimes the only thing I realized is that I am a stranger within them. Within my family history, there is a wild and tragic story that ends always with the goodness of God. What happens when small acts tamper with the story we all agreed to tell?